-

Scam Alert. Members are reminded to NOT send money to buy anything. Don't buy things remote and have it shipped - go get it yourself, pay in person, and take your equipment with you. Scammers have burned people on this forum. Urgency, secrecy, excuses, selling for friend, newish members, FUD, are RED FLAGS. A video conference call is not adequate assurance. Face to face interactions are required. Please report suspicions to the forum admins. Stay Safe - anyone can get scammed.

-

Several Regions have held meetups already, but others are being planned or are evaluating the interest. The Calgary Area Meetup is set for Saturday July 12th at 10am. The signup thread is here! Arbutus has also explored interest in a Fraser Valley meetup but it seems members either missed his thread or had other plans. Let him know if you are interested in a meetup later in the year by posting here! Slowpoke is trying to pull together an Ottawa area meetup later this summer. No date has been selected yet, so let him know if you are interested here! We are not aware of any other meetups being planned this year. If you are interested in doing something in your area, let everyone know and make it happen! Meetups are a great way to make new machining friends and get hands on help in your area. Don’t be shy, sign up and come, or plan your own meetup!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Want to borrow T-nuts that would fit a Bridgeport Table

- Thread starter Xyphota

- Start date

The thread is tapered on them to prevent the bolt going through and push up on the deck.

I'm guessing you already know that some are and some are not. You can buy both through threaded and part threaded T-nuts. I have some of each. I prefer the through threaded but that dictates extra care in use.

Yes, I've seen that method too, but I'm not sure its universal

Welcome back Peter. Where have you been?

When I make my own T nuts, I stake the threads at the bottom of the nut to stop the stud or bolt from going all the way through.

***If you make your own, it is important to do so, or else wen you are tightening, it is possible to break out you milling table. I've seen more than a few mills ruined this way. ***

***If you make your own, it is important to do so, or else wen you are tightening, it is possible to break out you milling table. I've seen more than a few mills ruined this way. ***

DPittman

Ultra Member

Why would you want through threads t nuts (unless you are using them for an entirely different purpose)?I'm guessing you already know that some are and some are not. You can buy both through threaded and part threaded T-nuts. I have some of each. I prefer the through threaded but that dictates extra care in use.

I have used carriage bolts with flats ground on each side of the cap head so it will fit the slot and also keep the bolt from turning when tightening.

When you make your own t nuts, make a couple with the threaded hole offset. they will come in handy for tight setups.

When you make your own t nuts, make a couple with the threaded hole offset. they will come in handy for tight setups.

I assume you mean the hole is closer to one end of the T nut than the other?When you make your own t nuts, make a couple with the threaded hole offset

Former Member

Guest

The T-nuts I have from various suppliers are not tapered that I'm aware of but have the threads staked on the bottom side preventing pass through. Staked for those that don't know is punched with chisel or center to crush a small portion of thread to prevent passing.

The ones I've made can pass through are only used with cap screws in specific application that does not allow the cap screw to bottom out.

The ones I've made can pass through are only used with cap screws in specific application that does not allow the cap screw to bottom out.

trlvn

Ultra Member

By accident, I found that the clamp kit I use with the mill/drill actually works well with my drill press. The T-nuts register in the slots in the drill press table. If the nuts were through-threaded (they're not), it would mean that there would not be studs sticking up and potentially getting in the way. OTOH, a 1/2" nut and a fender washer works quite well too.Why would you want through threads t nuts (unless you are using them for an entirely different purpose)?

Craig

trlvn

Ultra Member

This discussion prompted me to look at the things in my shop with T-slots: RF-30 mill/drill, 6 inch rotary table and Craftex CX706 lathe. As in my previous post, the slots in the drill press table are somewhat compatible with the T-slots in the mill/drill.

When I got the little rotary table, used, it didn't come with any hold-down hardware. I made a couple of special studs threaded 1/2-13 on the nut side and 3/8-16 to secure the rotary table to the mill/drill. The RoTab has 3/8 inch slots so I made a batch of T-nuts to fit it. At that point, I didn't realize there were so many sizes available and at relatively low cost.

The lathe is the latest addition to the shop. I haven't had a reason to use the T-slots in the cross-slide, yet. The slot measures about 0.400 inches and the other measurements are similarly beefier/heavier than the RoTab. However, the T-nuts from the RoTab fit in the lathe and appear to be quite compatible. That was a pleasant surprise!

Craig

When I got the little rotary table, used, it didn't come with any hold-down hardware. I made a couple of special studs threaded 1/2-13 on the nut side and 3/8-16 to secure the rotary table to the mill/drill. The RoTab has 3/8 inch slots so I made a batch of T-nuts to fit it. At that point, I didn't realize there were so many sizes available and at relatively low cost.

The lathe is the latest addition to the shop. I haven't had a reason to use the T-slots in the cross-slide, yet. The slot measures about 0.400 inches and the other measurements are similarly beefier/heavier than the RoTab. However, the T-nuts from the RoTab fit in the lathe and appear to be quite compatible. That was a pleasant surprise!

Craig

Why would you want through threads t nuts (unless you are using them for an entirely different purpose)?

First off, let me say that I agree with @Dabbler 100%. Staked or part threaded nuts are the safe and smart way to go.

But they are not complete protection from this issue.

Personally, I almost always prefer to use socket head cap screws carefully selected for each application over those horrible threaded studs you get in the kit.

The main reason I prefer them is not because I like the way they look (although they do look way better than a threaded stud). I like them because they have high quality threads that are very consistent with easily controlled torque characteristics.

I don't worry about bottoming out the screw because each application is carefully selected to make that impossible. But even more importantly, I never apply more torque than the cast iron can handle - regardless of whether or not the screw bottoms out.

Some history is appropriate here.

I got my first clamp set 50 plus years ago when I was using my drill press as a mill. It has thrust bearings and a chuck with a threaded retaining collar. It was basically a horrible milling machine but it was still infinitely better than nothing. The table is slotted and has an x pattern of drilled holes in the traditional way of drill press tables. There are no bottoms in the T-slots that a through bolt could bear against. I also bought an x-y table for it which had T-slots with bottoms.

When I mounted the x-y table to the drill press table, I discovered that some idiot had not tapped the T-nuts all the way through so I couldn't torque down the Bolts. So I bought a tap and finished the job properly. As a 20 year old I had no idea that there was a reason for the way those nuts were partially threaded like that and there was no internet yet to learn anything from.

That old drill press met my modest milling and drilling needs for forty years.

Perhaps by luck the much bigger Mill/Drill I got 40 years later (10 years ago) used the same size T-nuts so I used them and at some point I encountered the bolt bottom issue. To me it was just a simple artifact of a nut sliding in a cast iron T-slot. Not a lot different from a shallow drilled hole. I simply installed the bolt to the right depth first and then slid it into the slot to where I needed it. In so doing, the bolt also makes a handy handle to move the nut with. Occasionally I had to remove a bolt in situ. In particular, I had a few tools that had base mounting holes instead of flanges. In these cases, I would simply thread it in all the way by hand and then back it off. Life was good for 10 more years.

In the search for a better milling machine I bought two Bridgeport sized Knee Mills last year. But I had used up all my T-nuts at that point and needed a few more. So I ordered some from KBC. That's where and when I noticed that you could get them threaded through or partially threaded and my head was instantly filled with the big question WHY would anyone want partially threaded?

It's the exact opposite question from what you asked!

The magic of the internet answered that question fast. But with 50 years of experience using threaded through nuts behind me I ordered threaded through anyway. It's what I was used to. But by then I also had much more knowledge of the issues. Let me explain why.

Throughout my career I have more or less constantly had to deal with fasteners and their issues. Fasteners are so important to an automotive company that we had an entire department of fastener experts whose job it was to monitor the work of the various design groups, provide advice and information, do detailed analysis, develop new fastener technology, and approve fastener applications in vehicles. I learned a lot from them over the years. There is a lot more science that goes into a threaded connection than most of us realize.

While I totally agree with @Dabbler's advice for anyone using T-nuts, I would add a few other pieces of advice all aimed at the exact same problem arrived at by a different path.

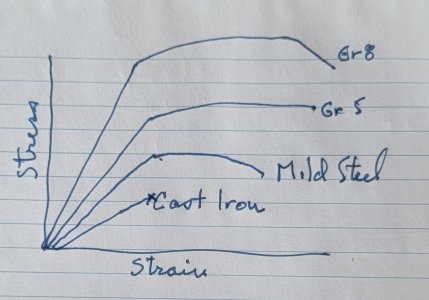

That T-slot in our mill tables is a vulnerable piece of hardware. You can break a piece off exactly as we have been discussing. But you can also break a piece out using a bridge clamp exactly the same way whether or not the nut is through threaded. You can also break it using a simple ear clamp or a bar clamp or for that matter ANY application where the part and table are not in contact with each other in a compressed column. Cast iron can easily handle a high compressed load. It cannot handle a high bending or tension load. The stress/strain relationship for cast iron is not a curve that bends. It is a line that ends .... at fracture.

Depending on the type of cast iron or steel, cast iron's yield strength is about half that of regular steel. In general, roughly 30,000 psi for regular cast iron vs 60,000 psi for regular steel or 130,000 for a grade 8 bolt.

Unless there is a pinched (compressed column) stack of metal between the top of the table and the bottom of the bolt head or nut, a tightened T-Nut bolt exerts the same kind of load on the T-slot as a through bolt that reaches the bottom of the slot. In other words, the half threaded nut protects you from a bolt run too deep, but it does nothing to protect you from a non-compressed joint.

A stacked compressed joint does not try to rip apart the top of the T-slot - instead it squeezes everything together. But a bridge connection, or a side clamp, or an ear clamp does. The worst of them is the bridge clamp. That's those long slotted forged bars that come in the clamping kit. They look like this:

The longer the bridge between compressed columns, the worse the problem.

To deal with this, I developed my own standard rule of thumb for using T-slot Fasteners. Never torque the fastener beyond the strength of the cast iron ear of the T-slot. The torque I use is just 10 ft pounds (120in-lb) on a lubricated 1/2-13 machine screw. I can also use a short Allen wrench tightened by hand but not gronked. 10 ft lbs generates 1500 pounds of clamping force and about 10,000 psi of stress in both the bolt and the cast iron T-slot. Although the T-slot has a, bigger cross sectional area, it is significantly reduced by the slot itself. The stress numbers I chose are conservative. I suppose I could use a higher number but I don't like to push things. I don't have access to any fastener experts anymore and I don't have a CAE Workstation to model the stress in the cast iron T-slot Ears. 10,000 sounds safe to me and 1500 pounds of clamping force per fastener seems like more than enough too.

So there you have it. That's really the reason that I don't worry about threaded through nuts myself.

For reference, these are my vise Clamps. They are oiled and tightened to 10 foot pounds each. Notice the nose in the vise groove. What you can't see in the photo is the foot opposite the nose and the gap between the clamp and the table under the screw. No unthreaded section in the T-Nut would stop that table from cracking if I overtightened that screw.

My advice to others is: 1. Use an unthreaded or crimped T-slot nut. 2. Regardless of the type of T-nut you use, never tighten the nut or bolt beyond 10 ft pounds unless you know exactly what you are doing. 3. Avoid high torque with bridged or nose end Clamps or any other uncompressed column.

Thanks @Susquatch for that excellent discussion. Sometimes I can be too terse, and I really appreciate someone that can tell the whole story.

I have one thing to add to the discourse: when you have an unstaked T nut, lubricated or not, and you use a bridge clamp (as illustrated), sometime the screw jams in the nut, and only turns in the t nut. This is caused by a little too much angle on the bridge clamp, and is far too common. This causes the 'terrible stud' to turn as instead, causing the stated problem.

Where possible (such as mounting my vises or index head) I *always* use Grd 8 custom length bolts, with custom washers. It is only a momentary sacrifice, but the bolts and washers stay forever with the vise, and there is no jury rigging. You always have the percect mount at hand, and is a lot faster than hunting down a flange nut and correct stud from the kit.

I have one thing to add to the discourse: when you have an unstaked T nut, lubricated or not, and you use a bridge clamp (as illustrated), sometime the screw jams in the nut, and only turns in the t nut. This is caused by a little too much angle on the bridge clamp, and is far too common. This causes the 'terrible stud' to turn as instead, causing the stated problem.

Where possible (such as mounting my vises or index head) I *always* use Grd 8 custom length bolts, with custom washers. It is only a momentary sacrifice, but the bolts and washers stay forever with the vise, and there is no jury rigging. You always have the percect mount at hand, and is a lot faster than hunting down a flange nut and correct stud from the kit.

@Susquatch does better math than me, I just know that unsupported t-nuts and a cast iron t-slot is a recipe for disaster.

Plus we all tend to think fasteners need way more torque than reality. If you need 150 ft-lbs of torque on your 3/8" t-nuts to stop your workpiece from moving, you're not using enough fasteners.

T-nuts and strap clamps can truly be your friends, just takes a little lateral thinking. To drastically eliminate the tension load on the cast iron t-slot, use a short clamp against the table and a bottom clamp nut. Also means the threaded rod doesn't flop all over the place and disturb your support arrangement when you loosen the top clamp nut.

Plus we all tend to think fasteners need way more torque than reality. If you need 150 ft-lbs of torque on your 3/8" t-nuts to stop your workpiece from moving, you're not using enough fasteners.

T-nuts and strap clamps can truly be your friends, just takes a little lateral thinking. To drastically eliminate the tension load on the cast iron t-slot, use a short clamp against the table and a bottom clamp nut. Also means the threaded rod doesn't flop all over the place and disturb your support arrangement when you loosen the top clamp nut.

Attachments

Thanks @Susquatch for that excellent discussion. Sometimes I can be too terse, and I really appreciate someone that can tell the whole story.

I have one thing to add to the discourse: when you have an unstaked T nut, lubricated or not, and you use a bridge clamp (as illustrated), sometime the screw jams in the nut, and only turns in the t nut. This is caused by a little too much angle on the bridge clamp, and is far too common. This causes the 'terrible stud' to turn as instead, causing the stated problem.

Where possible (such as mounting my vises or index head) I *always* use Grd 8 custom length bolts, with custom washers. It is only a momentary sacrifice, but the bolts and washers stay forever with the vise, and there is no jury rigging. You always have the percect mount at hand, and is a lot faster than hunting down a flange nut and correct stud from the kit.

And it looks better too! 😛

I can easily see what you describe happening. I think that's yet another downside of those horrible studs. Stuff like that happens. All of the studs from my kits are still in the rack. I used them once, barfed, and put them back.

FWIW, I buy 1/2", 3/8", & 1/4" machine screws at the local farm supply by the pound - usually longer length than I need. Then I cut and grind them to fit perfect as needed.

@Susquatch does better math than me, I just know that unsupported t-nuts and a cast iron t-slot is a recipe for disaster.

Plus we all tend to think fasteners need way more torque than reality. If you need 150 ft-lbs of torque on your 3/8" t-nuts to stop your workpiece from moving, you're not using enough fasteners.

T-nuts and strap clamps can truly be your friends, just takes a little lateral thinking. To drastically eliminate the tension load on the cast iron t-slot, use a short clamp against the table and a bottom clamp nut. Also means the threaded rod doesn't flop all over the place and disturb your support arrangement when you loosen the top clamp nut.

View attachment 25453

Perfect example of a fully compressed load setup with no danger of breaking the cast iron.

What it's doing all by itself there though is totally beyond me! 😉

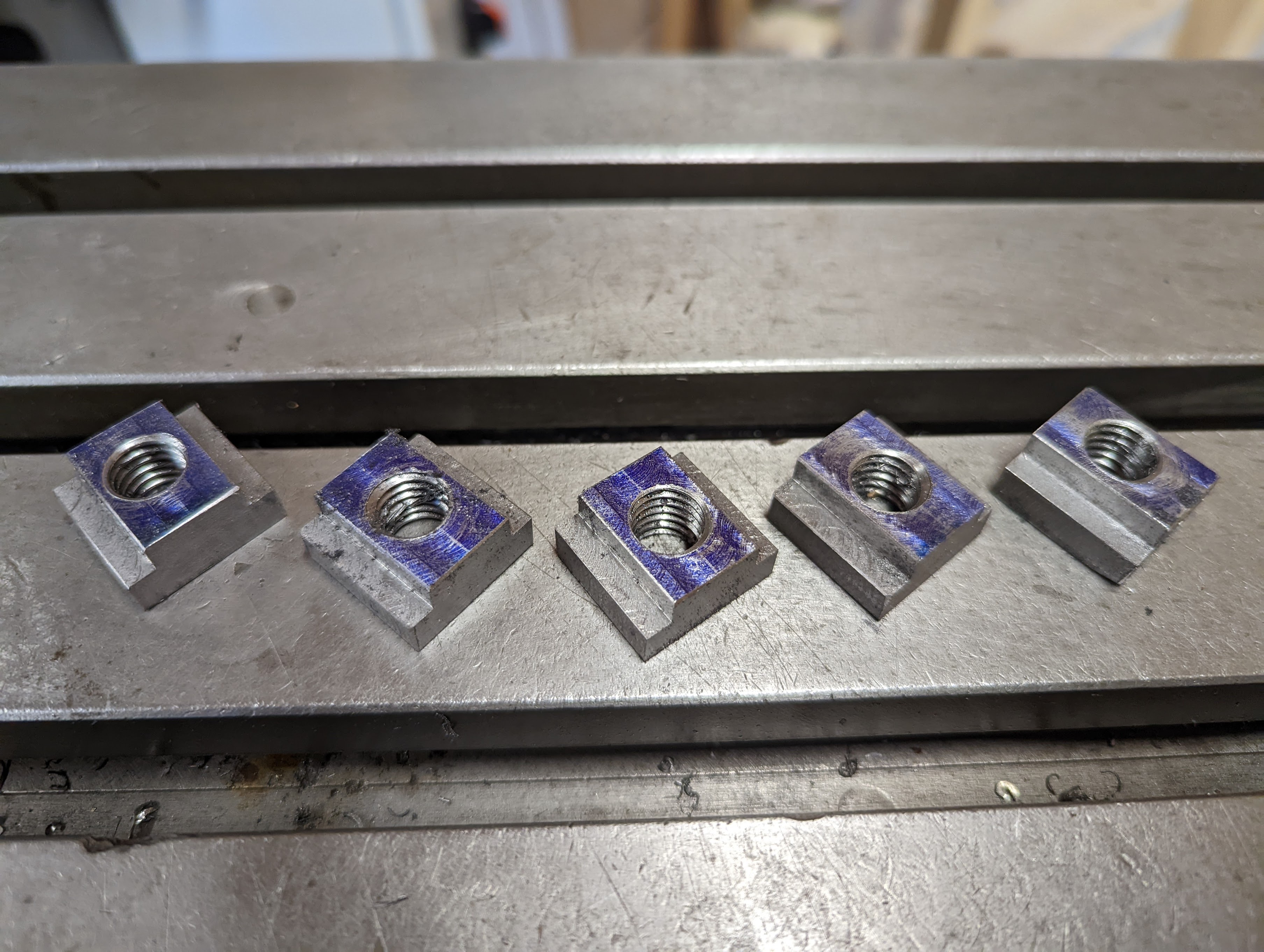

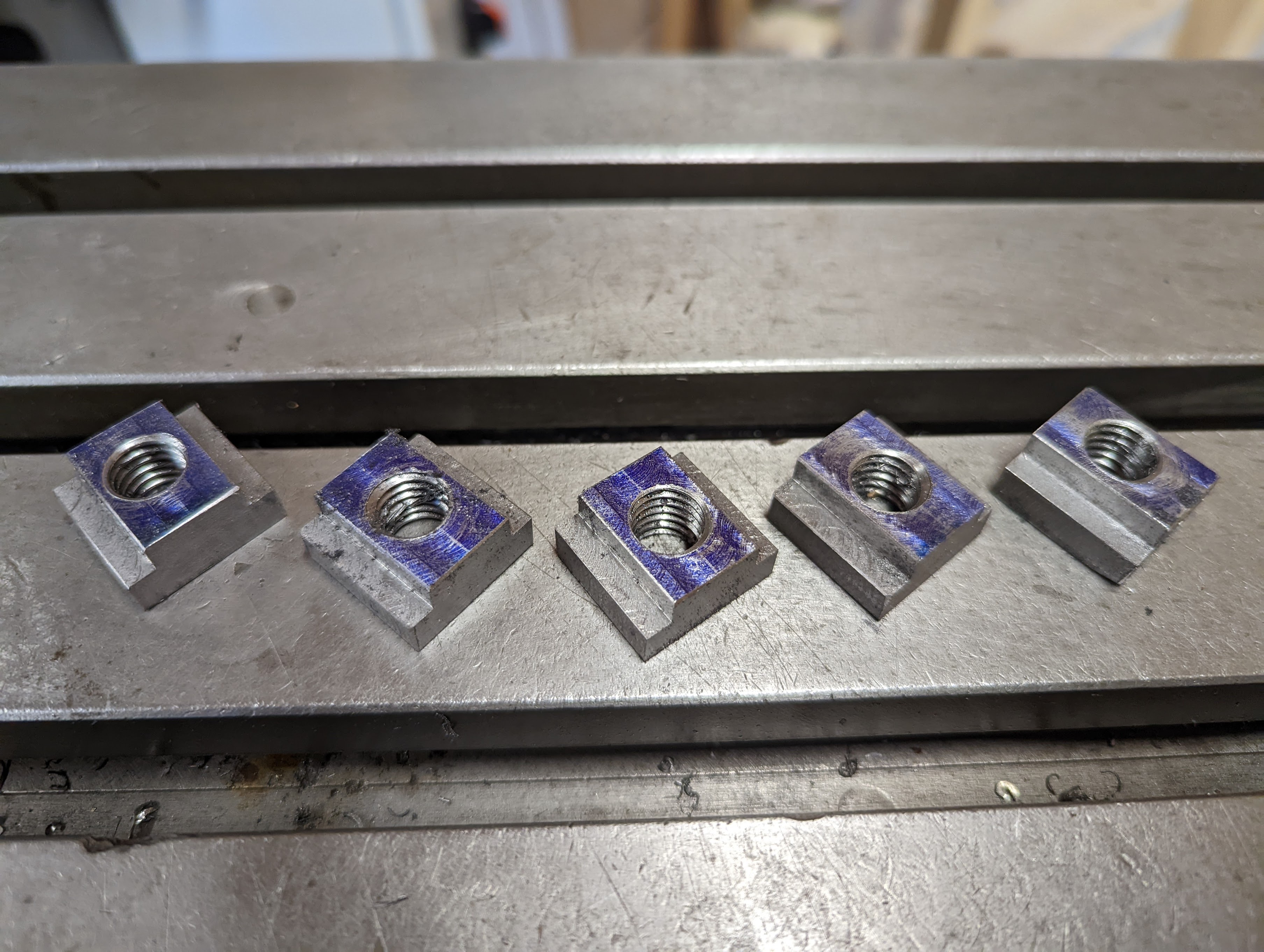

So this inspired me to make some t-nuts. I had some bar stock that I'd brought down to size breaking in my little power hammer a while back, and I figured this was just the use for near-dimension stock.

Not the prettiest toy soldiers, and, frankly unnecessary given I have a stap set... But I hit *almost* all my dimensions, including fixing a couple of close calls in the backlash department.

In the strap clamp horror stories though, this seems like the most over-worked length stop possible, but I had no way to hold a stop inboard of my vise jaws to take the little blocks to final length:

In retrospect I should have made 4 t-nuts 1.25" long instead of 5 at 1".

Still need to get some acetone and some blueing compound.

Not the prettiest toy soldiers, and, frankly unnecessary given I have a stap set... But I hit *almost* all my dimensions, including fixing a couple of close calls in the backlash department.

In the strap clamp horror stories though, this seems like the most over-worked length stop possible, but I had no way to hold a stop inboard of my vise jaws to take the little blocks to final length:

In retrospect I should have made 4 t-nuts 1.25" long instead of 5 at 1".

Still need to get some acetone and some blueing compound.

So this inspired me to make some t-nuts. I had some bar stock that I'd brought down to size breaking in my little power hammer a while back, and I figured this was just the use for near-dimension stock.

Not the prettiest toy soldiers, and, frankly unnecessary given I have a stap set... But I hit *almost* all my dimensions, including fixing a couple of close calls in the backlash department.

In the strap clamp horror stories though, this seems like the most over-worked length stop possible, but I had no way to hold a stop inboard of my vise jaws to take the little blocks to final length:

In retrospect I should have made 4 t-nuts 1.25" long instead of 5 at 1".

Still need to get some acetone and some blueing compound.

Wow! That is a wild setup!

But nice nuts! 😀

And a GREAT example of unsupported uncompressed load at the T-nuts.

But it's ok. Just don't tighten that top nut beyond 10 foot pounds oiled or you risk damaging your T-slot. Keep in mind that my recommendations are both my own and conservative. So you can prolly get away with more. But I wouldn't risk it. A broken table is a broken table. 10 foot pounds is 5,000 pounds in each column.That's a lot of force you don't really need more.

Yeah, since this isn't holding anything being actually milled, it's not particularly torqued down. No reason to.Just don't tighten that top nut beyond 10 foot pounds oiled or you risk damaging your T-slot.

I have used carriage bolts with flats ground on each side of the cap head so it will fit the slot and also keep the bolt from turning when tightening.

When you make your own t nuts, make a couple with the threaded hole offset. they will come in handy for tight setups.

@johnneilsen threaded offset t nuts, smart thinking and good planning.

@PaulL said 'In retrospect I should have made 4 t-nuts 1.25" long instead of 5 at 1". Still need to get some acetone and some blueing compound.

Suggestion for the length of material one would use you should do it again then you'll have short and long t nuts sets. After all you now have the experience of doing them and set up. Make a couple with offset threading while your at it, job done. Just saying!

Suggestion for the length of material one would use you should do it again then you'll have short and long t nuts sets. After all you now have the experience of doing them and set up. Make a couple with offset threading while your at it, job done. Just saying!

Last edited: