-

Scam Alert. Members are reminded to NOT send money to buy anything. Don't buy things remote and have it shipped - go get it yourself, pay in person, and take your equipment with you. Scammers have burned people on this forum. Urgency, secrecy, excuses, selling for friend, newish members, FUD, are RED FLAGS. A video conference call is not adequate assurance. Face to face interactions are required. Please report suspicions to the forum admins. Stay Safe - anyone can get scammed.

-

Several Regions have held meetups already, but others are being planned or are evaluating the interest. The Calgary Area Meetup is set for Saturday July 12th at 10am. The signup thread is here! Arbutus has also explored interest in a Fraser Valley meetup but it seems members either missed his thread or had other plans. Let him know if you are interested in a meetup later in the year by posting here! Slowpoke is trying to pull together an Ottawa area meetup later this summer. No date has been selected yet, so let him know if you are interested here! We are not aware of any other meetups being planned this year. If you are interested in doing something in your area, let everyone know and make it happen! Meetups are a great way to make new machining friends and get hands on help in your area. Don’t be shy, sign up and come, or plan your own meetup!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tiny Drill chuck

- Thread starter Tomc938

- Start date

gerritv

Gerrit

My stash is presently rather more modest. But July is birthday month, and I have committed to building a clock (in tandem is with a very good friend) starting later this month. Progress on that should release some funds from the CFO. No bargains on eBay unfortunately.

I really need to start selling my stash of Univac hw from the 1950/60's, core memory should raise a good pool as well.

gerrit

I really need to start selling my stash of Univac hw from the 1950/60's, core memory should raise a good pool as well.

gerrit

those are 10mm Derbyshire's. There is embarrassing large piles of 8mm, 12mm 20mm 5c 2J......it is a disease.

Its a very long wait for a complete set, great brand, great condition and low price. Despite how cheap I am and always prowling for a bargoon....collets are one area where you sometimes just have to pay up.

Its a very long wait for a complete set, great brand, great condition and low price. Despite how cheap I am and always prowling for a bargoon....collets are one area where you sometimes just have to pay up.

Last edited:

historicalarms

Ultra Member

So lets get to the real meat & potatoes of this thread....what is the bore..."all these tiny cannon balls " indicates to me a shotshell was disassembled....I've got a 25 lb sack of them for you if you do run low.But I have all these tiny little cannon-balls I want to use up!

Interesting. Enlighten me on a few things. As mentioned I don't own a pin vise but I see its in the typical watch/clock/jewelers tool arsenal. I always assumed must be for shallow depth holes in brass plate or something. What is a typical depth/diameter ratio you are doing with pin vise? How do you ensure the tool is perpendicular & stays that way for duration? For deeper holes and/or tougher materials, I assumed that's where those high end (high speed) specialized drill presses came into play? Clock stuff is outside my knowledge. I still don't know how they made accurate holes in ruby bushings 400 years ago LOLI'll be the dissenter on the speed thing. I think the speed notion comes from applying the cutting speed formula, but (for hss or carbon at least) that's just a theoretical maximum after which tool wear is non linear. Running below it is fine. I like speed for small drills, I have three high speed micro/sensitive drill presses that all see action, however I also drill them with a pin vise by hand or often very small holes in watchmakers lathe at say 1000 or 1500 rpm. Indeed, some of the smallests drills, say a .004" pivot hole, are often cut at hand power speeds - e.g. pivot drill lathes . Speed makes things go faster; but the cutting tool's performance and resultant hole can be just as good at a slow speed

Re rpm, yes I assume the high number comes from standard cutting speed formula. But are you saying that has more to do with tool life - as opposed to the feed rate would be proportionately, impractically slow at these diameters?

Interesting. Enlighten me on a few things. As mentioned I don't own a pin vise but I see its in the typical watch/clock/jewelers tool arsenal. I always assumed must be for shallow depth holes in brass plate or something. What is a typical depth/diameter ratio you are doing with pin vise? How do you ensure the tool is perpendicular & stays that way for duration? For deeper holes and/or tougher materials, I assumed that's where those high end (high speed) specialized drill presses came into play? Clock stuff is outside my knowledge. I still don't know how they made accurate holes in ruby bushings 400 years ago LOL

to be clear, I was only trying say that the operation, other than time, doesn't suffer from lower rpm. From watchmakers lathe at maybe 1500 to hand techniques, the guys drilling the smallest holes don't much worry about the rpm. I use a pin vise less frequently these days as the machine collection has gone up, but it is still handy for drilling in the watchmakers lathe. A typical approach would be to make a centre mark with a graver then drill with a pin vise, keep it straight by looking in twp planes. It never seems like there is the right tooling to hold stuff in the tailstock (its the rarer ones that take the same collect as the the headstock). Nowadays I have a better kit of gear so last few times i remember held the drill in the tailstock. depth/dia. don't know if there is rule of thumb, probably typically 2- 4x?

Also, the high speed drill presses get used, but I can't remember doing so for watch work....that (to the extent of my experience) is work in the round and happens in the lathe (and sometimes with a pin vise)

Tools like these are for pivoting, or drilling into a shaft to install a replacement pivot (that's watch parlance, journal bearing surface of a shaft o a mechanic) While some guys hook motors up to them, the tradition motive power is via a bow or hand crank. watch pivots can be very small.

I still don't know how they made accurate holes in ruby bushings 400 years ago LOL

The best watchmaking book ever, just happens to be by the best watchmaker ever: the late George Daniels. His book covers it as it occasionally its required today (by people close to his league). The only difference is today the machines have electric motors instead of bows or foot treadles. its basically make laps the right shape and cut the jewel with diamond paste. His is the only description I've read, mere mortals buy jewels from watch supply houses. btw, there is a copy GD's book on kijiji now, I think in Calgary. There is nothing else quite like it in that most of watchmaking is really watch repairing, whereas his book and skill is truly watchmaking.

Re rpm, yes I assume the high number comes from standard cutting speed formula. But are you saying that has more to do with tool life - as opposed to the feed rate would be proportionately, impractically slow at these diameters?

I'm saying its great if you have the speed, but no big deal if you don't. That the surface speed you get from the formula, for hss and carbon at least, is the theoretical maximum before the rate of tool wear vs material remove falls off. In other words there is a definite penalty for going faster, but none for going slower (except the job might take longer). If a watchmaker is making a 0.010" dia. hole, the theoretical speed is 40,000 rpm to get 100 feet per minute. In practice the watchmaker might run the lathe at say 1000 rpm or 2.5 feet per minute, and everything will come out fine

imo the key to drilling small holes is not breaking the bloody drill lol....and the two things that help with that are 1) sensitivity, and not quite a lap behind, 2) concentricity. Speed is well, a DNF lol (imo)

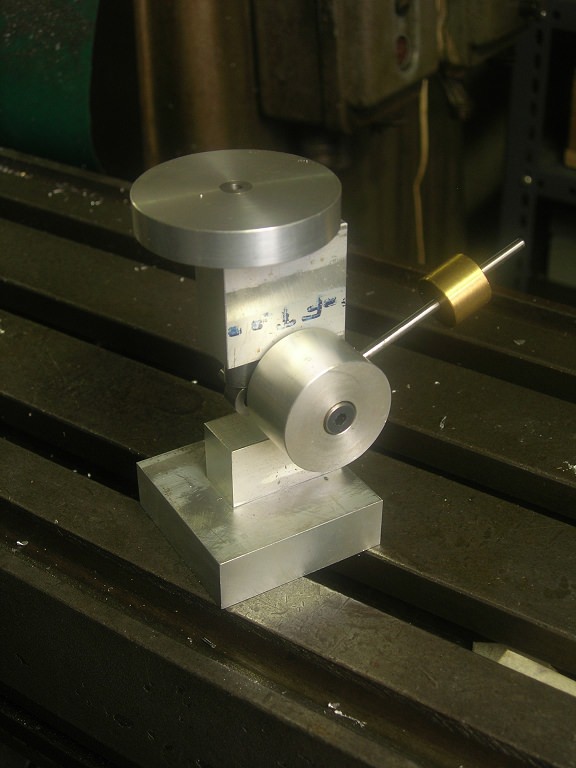

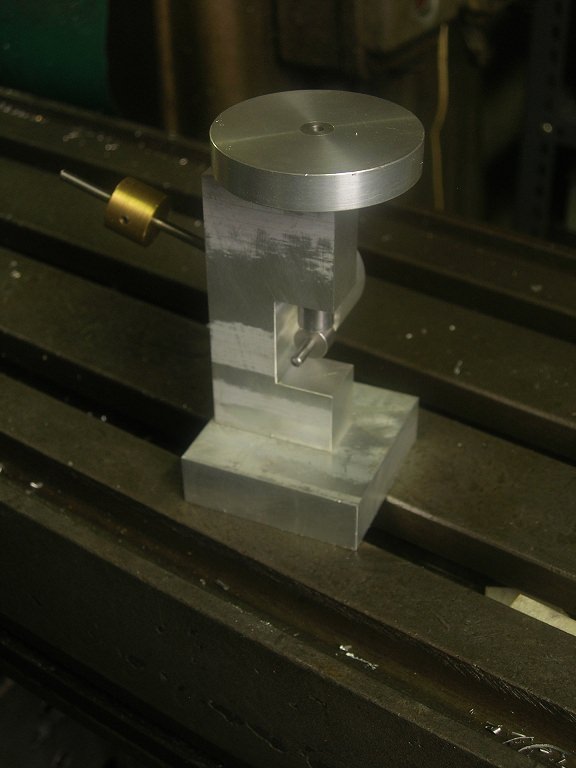

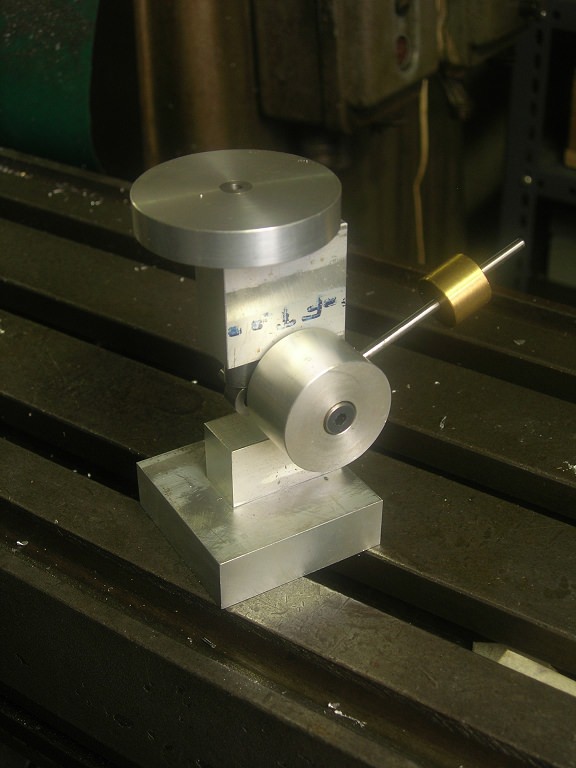

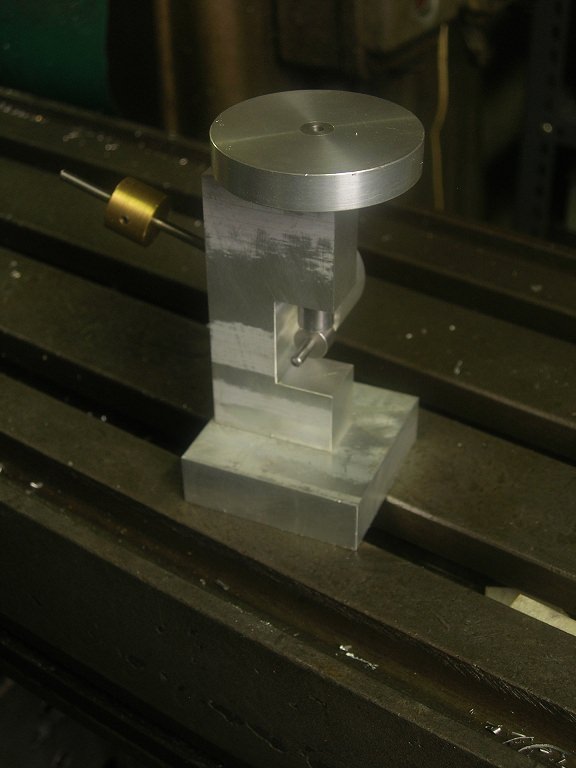

Concentricity is expensive, so you do the best you can (and the drills do have a lot of flex). The best sensitive drilling device I've seen is this one, the design of which appeared in Home Shop Machinist eons ago. The lever pivots on a shoulder bolt; other than that everything is visible and one could probably be built from the photos. I can't remember the designer name buts its better than any other sensitive drilling design I've seen. Build it with a thou clearance so it feels frictionless, set the brass counter balance and you can advance the work up into a rotating drill and about the only force you feel or have to overcome is the drilling op. A piece of masking usually suffices as a hold down.

Last edited:

Tom Kitta

Ultra Member

For small holes you need to "Feel" the drill - on a lathe you can do a floating chuck, where the chuck arbor is loose in another tube and you hold the chuck in your fingers.

For milling machines there is a spring loaded attachment for sensitive drilling - very expensive - or so I heard.

For milling machines there is a spring loaded attachment for sensitive drilling - very expensive - or so I heard.

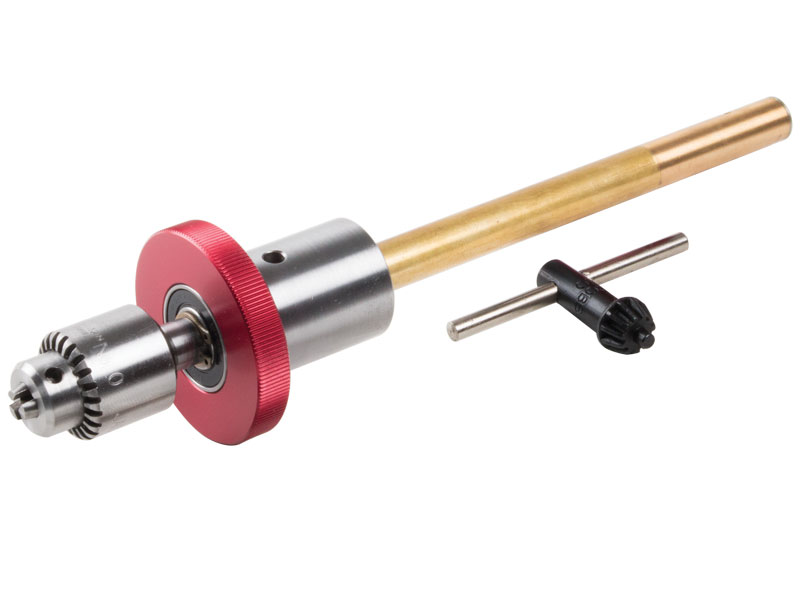

This is why I suggested the Albrecht/Sherline/Indian sensitive feed mechanism. Holding the drill bit is not that difficult as many here have shown, it's the issue of having sufficient feel to not break tiny bits that is a greater problem IMO. The quill down feed on a mill or mill/drill is fine for larger bits but a bit heavy-handed for tiny bits.For small holes you need to "Feel" the drill - on a lathe you can do a floating chuck, where the chuck arbor is loose in another tube and you hold the chuck in your fingers.

For milling machines there is a spring loaded attachment for sensitive drilling - very expensive - or so I heard.

Like most things the expense is proportional to the quality ($40 for new sans-chuck from India, $175 for new Sherline, and $250 - $400 for used Albrecht).

Dave

...

..The best sensitive drilling device I've seen is this one, the design of which appeared in Home Shop Machinist eons ago. The lever pivots on a shoulder bolt; other than that everything is visible and one could probably be built from the photos. I can't remember the designer name buts its better than any other sensitive drilling design I've seen. Build it with a thou clearance so it feels frictionless, set the brass counter balance and you can advance the work up into a rotating drill and about the only force you feel or have to overcome is the drilling op. A piece of masking usually suffices as a hold down.

That is a great little tool. As you know many of the small sensitive drill presses have lever-operated tables and fixed quills (opposite to the standard drill press where the quill moves vertically and the table/workpiece remains stationary). Making a little moving-table platform for use in a more common machine is brilliant ... and is now another thing for me to make

Thanks for posting.

Dave

Somehow I seem to miss out on cool threads like this.

FWIW, I think @Mcgyver is right that high speed is not required for small drills. I don't really know why. Perhaps it isn't about the rotational speed as much as it is the rate of advancement - ie the pressure on the end of the drill bit. Which in psi is HUGE! What I do know is that I drill lots of teeny tiny little holes in things all the time - by hand using a pin vise. It works just fine.

The subject reminds me that Joe Pie did a video on drilling small holes on the lathe with his own drill adapter and a Jacobs Zero Chuck.

A similar video shows the use of a similar adapter (an accu feed drill adapter) also with a Jacobs Zero Chuck being used on a mill.

The accu feed drill adapter is prolly one of the "expensive" devices that @Tom Kitta refers to. I see that it is available from KBC for just over a hundred bucks.

www.kbctools.ca

www.kbctools.ca

Ignore the cat40 specifications. The manufacturer says its a 1/2 stud that can be held in a collet or a half inch drill chuck.

What I would like to have is something that will work on both a lathe AND on a mill. The lathe device is easier to do because the chuck doesn't spin, but in both cases, the collar only provides thrust so the mill device should work on the lathe but not vice-versa. Am I missing something?

I also like @Mcgyver 's little lift table. Who cares if it is the quill lowering the bit or the table raising the part. A sensitive table is just as good as a sensitive chuck holder. And I really don't think the part needs to be held in a vise when any of us could snap the drill with torque from our hands without even thinking about it.

FWIW, I think @Mcgyver is right that high speed is not required for small drills. I don't really know why. Perhaps it isn't about the rotational speed as much as it is the rate of advancement - ie the pressure on the end of the drill bit. Which in psi is HUGE! What I do know is that I drill lots of teeny tiny little holes in things all the time - by hand using a pin vise. It works just fine.

The subject reminds me that Joe Pie did a video on drilling small holes on the lathe with his own drill adapter and a Jacobs Zero Chuck.

A similar video shows the use of a similar adapter (an accu feed drill adapter) also with a Jacobs Zero Chuck being used on a mill.

The accu feed drill adapter is prolly one of the "expensive" devices that @Tom Kitta refers to. I see that it is available from KBC for just over a hundred bucks.

SIERRA AMERICAN,SIERRA AMERICAN ACCU-FEED DRILL ADAPTER,2-009-AD100,KBC Tools & Machinery

SIERRA AMERICAN,SIERRA AMERICAN ACCU-FEED DRILL ADAPTER,2-009-AD100,KBC Tools & Machinery

Ignore the cat40 specifications. The manufacturer says its a 1/2 stud that can be held in a collet or a half inch drill chuck.

What I would like to have is something that will work on both a lathe AND on a mill. The lathe device is easier to do because the chuck doesn't spin, but in both cases, the collar only provides thrust so the mill device should work on the lathe but not vice-versa. Am I missing something?

I also like @Mcgyver 's little lift table. Who cares if it is the quill lowering the bit or the table raising the part. A sensitive table is just as good as a sensitive chuck holder. And I really don't think the part needs to be held in a vise when any of us could snap the drill with torque from our hands without even thinking about it.

Yup. And to use your reduced rpm example, at 2.5 fpm, that would equate to almost 2 minutes duration drilling a shallow 1/16" hole whereas maybe or 'normal' instinct would be a few seconds duration. Which would be equivalent to over-feeding. I've often wondered if peck drilling (success) had more to do with effectively slowing down the average DOC with interrupted paused cuts. Increased chip clearance probably helps too. Pecking seems to work, or at least I get straighter holes in high depth/diameter holes in the teeny sizes.If a watchmaker is making a 0.010" dia. hole, the theoretical speed is 40,000 rpm to get 100 feet per minute. In practice the watchmaker might run the lathe at say 1000 rpm or 2.5 feet per minute, and everything will come out fine

I also hold a view that lots of people 'successfully' drill deep skinny holes, but typically don't measure hole position on the back side. The drill may have penetrated the material OK, but It also may have drifted off some multiple of diameter. If the backside target wasn't a concern, well lucky you. But there are many other examples where the resultant exit hole position is important. I wonder out loud if the people who love HSS & curse carbide is maybe HSS might be more forgiving & bending whereas $$ carbide goes snap because it can't tolerate as much bend? I experienced this firsthand. I was having trouble with tiny carbides thinking they were defective whereas HSS was drilling (but slightly oversized), same sized cutter. Turns out my tailstock was out a couple thou. Dialed it back in & no more carbide problems. Perfect holes.

Cool links, thanks!

So getting back to chucking pin vises which then hold a small drill, everything I see has a knurled or some kind of 'gription' surface intended for manual holding. This is the reason why I'm skeptical that holding it in a chuck didn't look like reliable way to achieve low runout. Unless maybe a 4J & dialing it in.

I thought maybe like these but the description infers just another form of handle.

www.starrett.com

www.starrett.com

Are there other products out there intended to be used this way?

I thought maybe like these but the description infers just another form of handle.

S166 Pin Vise Set

The Starrett 166 Series Pin Vise has an insulating PVC handle which is octagonally shaped, preventing it from rolling when laid down. Pin Vise SET, Sizes 166A/B/C/D down. <br/><br/>Note:<br/>This item is discontinued. Please consider the recommended alternative listed above or contact our...

Are there other products out there intended to be used this way?

Attachments

Hi McG: I have a set of these, but they were badly stored in wood with humidity. They hurt my feelings for appearance, but have never failed me. I would like to find a shiny set. If you ever come across another set, please give me a heads up. I have a very nice BB Derby with a quick release collet holder, lever tailstock, cross slide, QCTP of my own making and lots of misc. collets. But the main set is corroded, sigh. Regards, Ian Mossjust pop down to the Hasty Mart and grab a set of these

Hi Ian,

That's a shame about the corrosion. Its not affecting the ID's or taper section? If not, maybe they'd polish up?

Serendipity will bring you set, how I got these...mentioned it enough and a friend of a friend was found.

...but it was a long wait, took years . Its for a Levin 10mm - list price of the set new is like 30,000 CDN. metric from .1 to 8 and imperial by 64th's. I guess if you are making some super expensive medical or aerospace device its no big deal but it means its not doable for home shop guys. I couldn't stomach the cash outlay even for used prices and I ended up trading a reconditioned (by me) older Schuablin 70 (sweat equity collets). The two are of about equal value, although I've been working for around $0.25/hour finishing the Schaublin. Most of my shop has been put together slowly for small dollars but with items like that set that rare and pristine imo you have to pounce when you see it.

If I see another set I'll let you know.

That's a shame about the corrosion. Its not affecting the ID's or taper section? If not, maybe they'd polish up?

Serendipity will bring you set, how I got these...mentioned it enough and a friend of a friend was found.

...but it was a long wait, took years . Its for a Levin 10mm - list price of the set new is like 30,000 CDN. metric from .1 to 8 and imperial by 64th's. I guess if you are making some super expensive medical or aerospace device its no big deal but it means its not doable for home shop guys. I couldn't stomach the cash outlay even for used prices and I ended up trading a reconditioned (by me) older Schuablin 70 (sweat equity collets). The two are of about equal value, although I've been working for around $0.25/hour finishing the Schaublin. Most of my shop has been put together slowly for small dollars but with items like that set that rare and pristine imo you have to pounce when you see it.

If I see another set I'll let you know.

This is why I suggested the Albrecht/Sherline/Indian sensitive feed mechanism. Holding the drill bit is not that difficult as many here have shown, it's the issue of having sufficient feel to not break tiny bits that is a greater problem IMO. The quill down feed on a mill or mill/drill is fine for larger bits but a bit heavy-handed for tiny bits.

The cost of the Sherline is $120 US but it includes a chuck. I cant figure out if this will fit an R8 spindle using a larger chuck or a collet, and I can't figure out if it will fit an MT3 lathe tailstock with a suitable drill chuck or collet either. It seems to be purpose made for a Sherline mill with a screw on spindle nose.

Sensitive Drilling Attachment - Sherline Products

Here is the Sierra American Accu drill. It looks like it can be chucked in a half inch drill chuck or a half inch Collet. It is $105 Cdn at KBC but does not include a chuck.

SIERRA AMERICAN,SIERRA AMERICAN ACCU-FEED DRILL ADAPTER,2-009-AD100,KBC Tools & Machinery

SIERRA AMERICAN,SIERRA AMERICAN ACCU-FEED DRILL ADAPTER,2-009-AD100,KBC Tools & Machinery

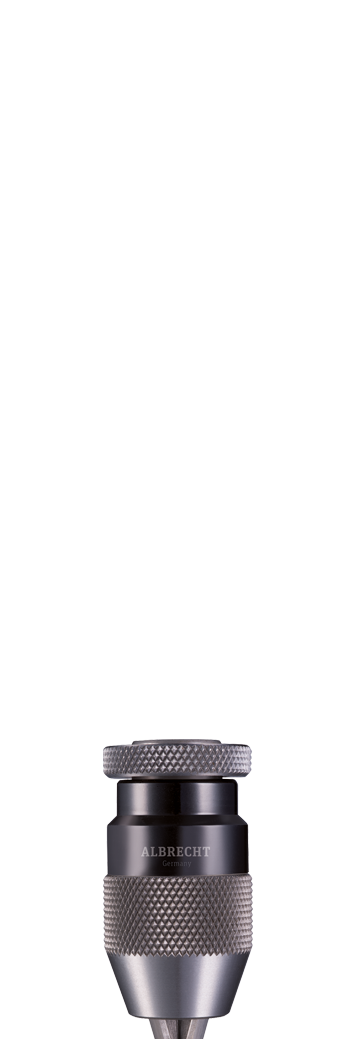

The Albrecht looks like it comes in an R8 with a chuck or a straight shank without a chuck, but it isn't totally clear to me what is what. The chuck is only spec'd down to 1mm which would not be small enough for my needs. I think it might be necessary to contact them. I could not find pricing.

1st

Albrecht Germany Präzisions Spannfutter und Bohrfutter. Ein Albrecht APC ist derzeit das schnellste, fräserschonendste und sicherste Spannfutter der Welt.

I found several products that might be described as the Indian version.

The first is available from amazon for $105 but looks like it only works on an mt3 lathe tailstock.

Sensitive Drill Attachment MT3 for Fine Drilling by Mounting B16 Drill Chuck : Amazon.ca: Tools & Home Improvement

Sensitive Drill Attachment MT3 for Fine Drilling by Mounting B16 Drill Chuck : Amazon.ca: Tools & Home Improvement

www.amazon.ca

The second looks like the Accu drill but comes from India with a chuck that goes down to 0.3mm. Looks like you could get a better MT0 chuck for it if you want. It is $60 (plus shipping) on amazon with the chuck.

Micro Drill Adapter Miniature Quill 1/2" Shank with JT0 Drill Chuck 0.3-4 mm-Manual Feed Control Avoids Drill Breakage Milling Tools (With Chuck) : Amazon.ca: Industrial & Scientific

Micro Drill Adapter Miniature Quill 1/2" Shank with JT0 Drill Chuck 0.3-4 mm-Manual Feed Control Avoids Drill Breakage Milling Tools (With Chuck) : Amazon.ca: Industrial & Scientific

www.amazon.ca

Here is the same unit without the chuck for $36 plus shipping on amazon.

Micro Fine Drill Adaptor Miniature Quill 1/2" Shank-JT0 Taper to mount Drill Chuck-Manual Feed Control-Avoids Breakage Machine Tools (Drill Chuck not included) : Amazon.ca: Tools & Home Improvement

Micro Fine Drill Adaptor Miniature Quill 1/2" Shank-JT0 Taper to mount Drill Chuck-Manual Feed Control-Avoids Breakage Machine Tools (Drill Chuck not included) : Amazon.ca: Tools & Home Improvement

www.amazon.ca

The third was REALLY INTERESTING!!! It appears to be a little machine shop product made in the USA being sold in India for 26579 Rupees!!! Converting from Rupees to Cdn, it was $450 assuming I did it right.

I also found this last one on little machine shop too for $142US. Looks like they get shafted in India even more than we do! This is a tough one to figure out......

Edit - no idea why some links show photos, some don't, some include a description, some don't. Click on em anyway. They do work.

gerritv

Gerrit

FYI the one on Desert Cart says it is imported from US, from Little Machine Shop. So that and the last link are in fact the same item.

No where on the LMS site does it say Made in USA so it definitely isn't made there.

As such, this is a better value: https://www.ebay.ca/itm/353272392428

Looking on eBay there are also options to buy from US at >$500 for the same item. Plus 100 in shipping and charges.

Gerrit

No where on the LMS site does it say Made in USA so it definitely isn't made there.

As such, this is a better value: https://www.ebay.ca/itm/353272392428

Looking on eBay there are also options to buy from US at >$500 for the same item. Plus 100 in shipping and charges.

Gerrit

FYI the one on Desert Cart says it is imported from US, from Little Machine Shop. So that and the last link are in fact the same item.

No where on the LMS site does it say Made in USA so it definitely isn't made there.

The first part of your note is exactly what I said. Then I commented on the huge price difference for the same thing from the same place.

You are probably right about your second comment. How ironic would that be! Made in China, shipped to little machine shop in the USA, then exported to India at a huge markup! What a crazy world we live in!

As such, this is a better value: https://www.ebay.ca/itm/353272392428

This is exactly the same item as my 5th link but 7$ more.

Edit - actually the same price! Apparently Amazon's price went up 7 bucks between now and when I posted this. I thought they NEVER did that! LOL!

I'm leaning toward getting the chuck separate from the tool so I can use smaller drills.

So, which one would you buy?

Thanks for that. I used to make parts for a special valve for gas chromatography instruments. I have a microscope with a traveling stage mounted above the lathe bed so that I can measure the length of cuts to .ooo1" while reducing a section of .114" dia. SS tubing to a wall thickness of .005". Lots of fun and got paid well for it too. Do you have duplicates of 12mm collets? I have a (believe it or not), Canadian made contact lens lathe that I occasionally use to make ball end finials for antique wooden flutes. I only have a couple 12mm, although I have made a 12-10 reducer that helps somewhat.Hi Ian,

That's a shame about the corrosion. Its not affecting the ID's or taper section? If not, maybe they'd polish up?

Serendipity will bring you set, how I got these...mentioned it enough and a friend of a friend was found.

...but it was a long wait, took years . Its for a Levin 10mm - list price of the set new is like 30,000 CDN. metric from .1 to 8 and imperial by 64th's. I guess if you are making some super expensive medical or aerospace device its no big deal but it means its not doable for home shop guys. I couldn't stomach the cash outlay even for used prices and I ended up trading a reconditioned (by me) older Schuablin 70 (sweat equity collets). The two are of about equal value, although I've been working for around $0.25/hour finishing the Schaublin. Most of my shop has been put together slowly for small dollars but with items like that set that rare and pristine imo you have to pounce when you see it.

If I see another set I'll let you know.

The cost of the Sherline is $120 US but it includes a chuck. I cant figure out if this will fit an R8 spindle using a larger chuck or a collet, and I can't figure out if it will fit an MT3 lathe tailstock with a suitable drill chuck or collet either. It seems to be purpose made for a Sherline mill with a screw on spindle nose.

Sensitive Drilling Attachment - Sherline Products

www.sherline.com

Yes, I see that now. It looked like a straight-shank when I glanced quickly, sorry for any distraction.

The Albrecht looks like it comes in an R8 with a chuck or a straight shank without a chuck, but it isn't totally clear to me what is what. The chuck is only spec'd down to 1mm which would not be small enough for my needs. I think it might be necessary to contact them. I could not find pricing.

1st

Albrecht Germany Präzisions Spannfutter und Bohrfutter. Ein Albrecht APC ist derzeit das schnellste, fräserschonendste und sicherste Spannfutter der Welt.www.albrecht-germany.com

The Albrecht sensitive feed does come in a straight-shank version that could be held in a collet (that's what I do with my Indian version) :

ø13|Zylinderschaft

Albrecht Germany Präzisions Spannfutter und Bohrfutter. Ein Albrecht APC ist derzeit das schnellste, fräserschonendste und sicherste Spannfutter der Welt.

They also used to spec their chucks down to 0 but now I see 0.2mm is as small as they claim on their "first chuck" (what I am familiar with) :

0.2 - 3.0 mm

Albrecht Germany Präzisions Spannfuter und Bohrfutter. Ein Albrecht APC ist derzeit das schnellste, fräserschonendste und sicherste Spannfutter der Welt.

And you don't want to find pricing

Dave <-- buys used off ebay