Ok, here’s a question for one of our members who has lots of letters after their name. P.Eng would be good for a start.

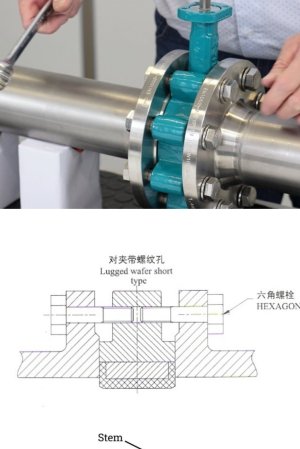

I have a project that needs a lot of butterfly valves. Lug butterfly valves have tapped bolt holes in a cast iron or ductile iron body. These valves are sandwiched between pipe flanges, and fastened with hex head bolts from each side.

A very common problem with ham-fisted pipe fitters is they use bolts that are too long, and the bolts contact in the tapped bolt holes. Fitter can’t get the bolts to tighten down to contact the flange face, so they get a cheater bar and give ‘er. This immediately breaks the valve body. Typical failures are stripped bolt holes, a cracked valve body, or in cast iron valves a wedge-shaped chunk of the outer lug breaks off.

So I intend to use full-thread studs from each side, threading in the studs until they touch, then backing off a bit for clearance. Then tighten a nut on the stud to contact the flange face. Like IMG_0196 below, but studs instead of hex head bolts.

My thinking is using studs from each side means even if the studs meet in the tapped bolt holes, tightening the nuts puts the studs in tension and relieving any possible over-loading of the valve body. My unschooled understanding of torque and friction is the friction between the nut and flange face is higher than the friction between the nut and stud, so the torque on the nut is putting a greater percentage of force into stretching the stud rather than forcing the two studs together, unlike using two hex head bolts in contact.

Does this make sense?

I have a project that needs a lot of butterfly valves. Lug butterfly valves have tapped bolt holes in a cast iron or ductile iron body. These valves are sandwiched between pipe flanges, and fastened with hex head bolts from each side.

A very common problem with ham-fisted pipe fitters is they use bolts that are too long, and the bolts contact in the tapped bolt holes. Fitter can’t get the bolts to tighten down to contact the flange face, so they get a cheater bar and give ‘er. This immediately breaks the valve body. Typical failures are stripped bolt holes, a cracked valve body, or in cast iron valves a wedge-shaped chunk of the outer lug breaks off.

So I intend to use full-thread studs from each side, threading in the studs until they touch, then backing off a bit for clearance. Then tighten a nut on the stud to contact the flange face. Like IMG_0196 below, but studs instead of hex head bolts.

My thinking is using studs from each side means even if the studs meet in the tapped bolt holes, tightening the nuts puts the studs in tension and relieving any possible over-loading of the valve body. My unschooled understanding of torque and friction is the friction between the nut and flange face is higher than the friction between the nut and stud, so the torque on the nut is putting a greater percentage of force into stretching the stud rather than forcing the two studs together, unlike using two hex head bolts in contact.

Does this make sense?